F

Washington puts hawk from Tri-Cities area on endangered species list. Wind turbines partly to blame.

Annette Cary, Tri-City Herald (Kennewick, Wash.) 8/28/2021

Aug. 28—The largest hawk in North America has been declared an endangered species in Washington state as fewer of them have been breeding in Benton and Franklin counties.

Friday the Washington state Department of Fish and Wildlife Commission voted unanimously to move the ferruginous hawk from the state’s threatened species list to endangered. status.

The change will bring more visibility toward the decline of the species, said Commissioner Kim Thorburn. It also could prompt more steps to protect the hawks.

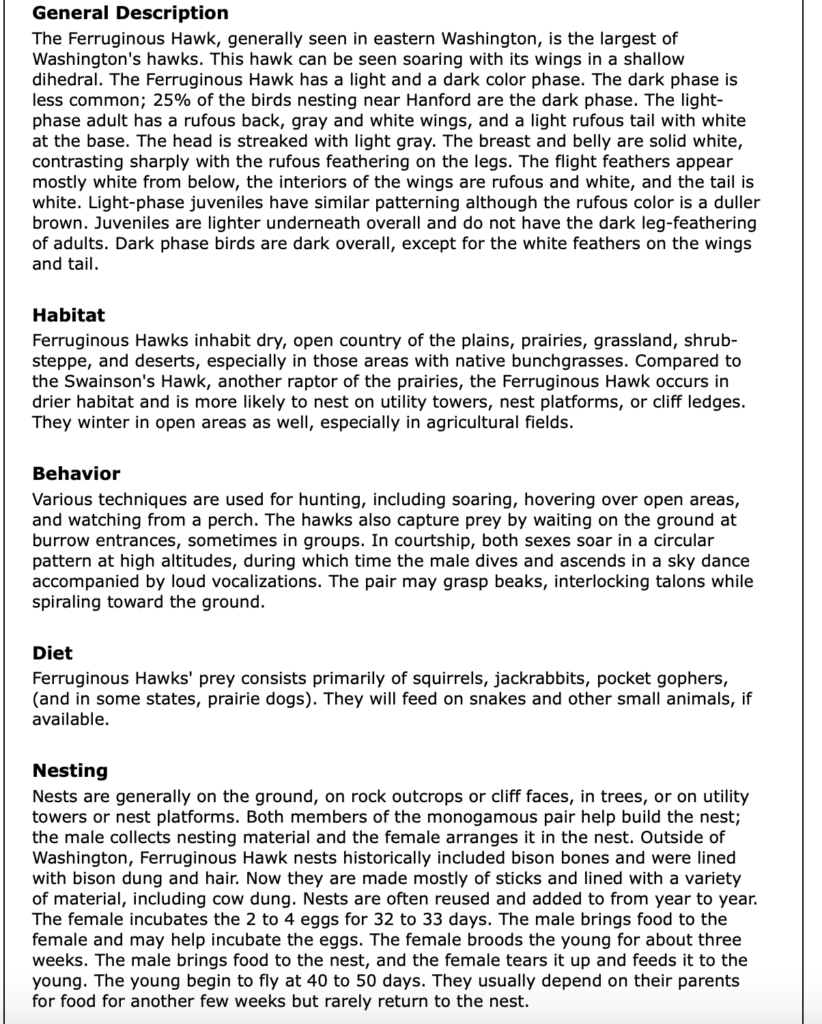

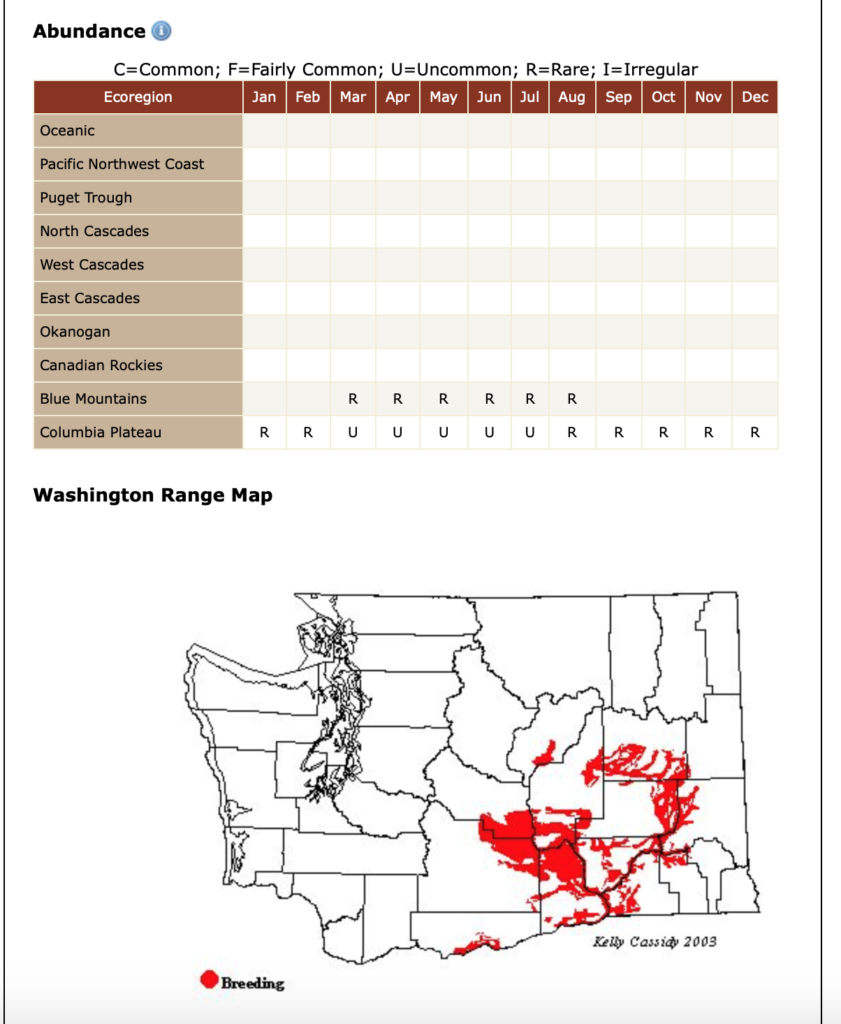

The ferruginous hawks spend about a third of the year in breeding territories, with Benton and Franklin counties the core breeding area in Washington state.

The hawks seek out grasslands and shrub-steppe in Eastern Washington to nest and raise their young

“Ferruginous hawks have been in trouble for decades,” said Taylor Cotten, conservation assessment section manager at the Washington state Department of Fish and Wildlife, earlier this year.

The ferruginous hawks were common in the early 1990s in several Eastern Washington counties, according to a draft review of the hawks in Washington state released earlier this year by the Washington state Department of Fish and Wildlife.

A study in 1926 described many old nests made of sticks in the Kiona-Benton City area and said they were most common near the Columbia and Yakima Rivers.

But between 1992 and 1995 the average number of breeding pairs nesting in the state dropped to 55. The last statewide survey conducted in 2016 found just 32 breeding pairs.

“Between 1974 and 2016, there have been significant declines in nesting territory occupancy, nest success and productivity,” the draft review said.

Loss of prey, habitat

The decline in Eastern Washington has been driven by several factors, including the development of land in the Tri-Cities area.

Over half of Washington’s original shrub-steppe had been converted to agriculture land by 1986, leaving remaining habitat in fragmented segments, the draft review said.

Wildfires also have degraded habitat in Eastern Washington.

The loss of abundant jackrabbits and ground squirrels as prey for ferruginous hawks, not just in Washington state but also in their late summer and winter ranges, is likely a significant factor in the declining number of breeding pairs in Eastern Washington, the draft review said.

Ferruginous hawks are reddish brown, but their underside is white. As they fly overhead, the birds appear white with black markings, including “commas” toward the end of their wings. Heads are brown with creamy streaking.

Adults can be as large as 27 inches from top of the head to tail tip and the wingspan can be nearly five feet.

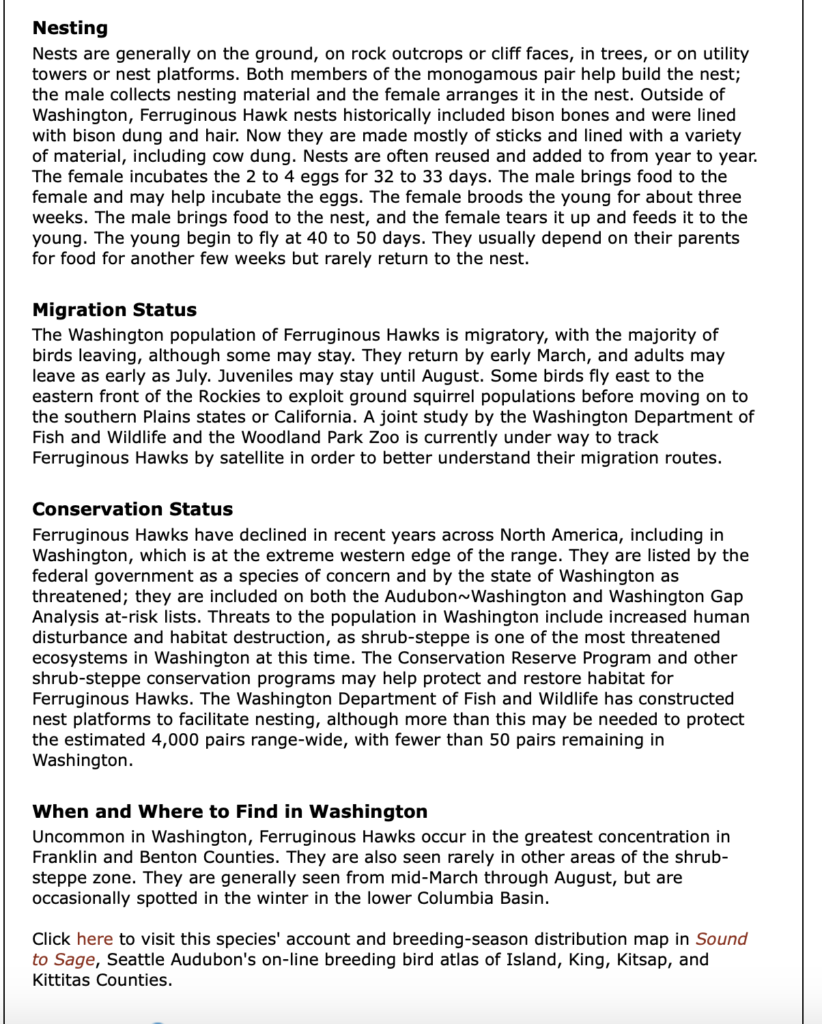

Most ferruginous hawks overwinter in California before migrating north in the spring to breed. They leave Eastern Washington in late July to spend late summer and fall in the southern Canadian provinces, Montana and western plains.

Wind turbines may have also played a role in the decline of breeding pairs, the draft review said.

Five ferruginous hawks are known to have died from turbine strikes along the Columbia River between 2003 and 2012, with that count likely low, according to the draft review.

Hawks and wind farms

One study found that the greater the density of wind turbines in north-central Oregon the lower the survival of young hawks in the area.

The Washington state Department of Fish and Wildlife raised concerns about ferruginous hawks and other wildlife in comments on the Horse Heaven Wind Farm proposed for Benton County that the agency submitted this spring to the Washington Energy Facility Site Evaluation Council.

Although most of the land for the proposed wind farm is on dryland wheat fields, many of the turbines, transmission lines and solar arrays are close to or cross over draws and canyons with shrub steppe and grassland habitats, the Department of Fish and Wildlife said.

In addition, the ridgeline of the Horse Heaven Hills is an important foraging area for raptors, it said.

The Horse Heaven ridgeline is among the last remaining functional and uninterrupted shrub-steppe and natural grasslands in Benton County, it said.

“Maintaining sufficient foraging area to support successful territories and nesting for ferruginous hawks and other raptors that use thermals and air currents associated with the Horse Heaven Hills seems particularly challenging with current proposed structure orientation,” Washington state Fish and Wildlife said in its comments.

Ferruginous hawks are not listed under the federal Endangered Species Act, but were listed as threatened as early as 1983 in Washington state. They also are listed as threatened in Canada.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Bird Species of Concern in the Horse Heaven Hills

The following is from the Seattle Audubon Society guide book. It lists the ferruginous hawks as “threatened” in WA State with the greatest concentrations seen in Benton and Franklin County.

Migrating birds follow the ridges and hills on their paths to winter or summer resting grounds. They use the uplift from warm air rising on the slopes the same way as a glider pilot uses it to gain elevation. During migration in the spring and fall, many birds of prey can be seen circling above the wind farms. Many get killed as they collide with the giant rotating blades of the wind turbines. According to a recent study done by the Wildlife Society, 573,000 birds are killed every year by wind farms.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Migrating Birds Use the Ridges

Scout Clean Energy claims they choose the sites of their wind farms with birds in mind and make sure they’re doing all they can to prevent wildlife deaths. However, it is hard to justify placing 23 miles of wind turbines on ridges and claim they are doing everything to save the migrating birds. Birds need the ridges to gain elevation on their long path of migration and the way to save them is to place the wind farms far away from ridges and hills.

A flock of 10 white pelicans is circling above this wind turbine at Nine Canyon

——————————————————————————————————————————————

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act, Explained

Don’t know what the MBTA even is? Here’s your comprehensive guide to the Act—including why it’s at risk.

By National Audubon Society, January 26, 2018

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA), signed into law in 1918, is among the oldest wildlife protection laws on the books. Its creation was one of the National Audubon Society’s first major victories, and in the years since its enactment, the MBTA has saved millions, if not billions, of birds.

But despite its importance in the history of the conservation movement, many people may not really know what the MBTA is, what it protects, and what kinds of activities fall under the law. Read on to find out more about the MBTA, why it’s at risk right now, and how Audubon is working to protect this most vital of environmental laws.

What is the Migratory Bird Treaty Act?

Stated most simply, the MBTA is a law that protects birds from people. When Congress passed the MBTA in 1918, it codified a treaty already signed with Canada (then part of Great Britain) in response to the extinction or near-extinction of a number of bird species, many of which were hunted either for sport or for their feathers. According to the USFWS: “The MBTA provides that it is unlawful to pursue, hunt, take, capture, kill, possess, sell, purchase, barter, import, export, or transport any migratory bird, or any part, nest, or egg or any such bird, unless authorized under a permit issued by the Secretary of the Interior. Some regulatory exceptions apply. Take is defined in regulations as: ‘pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or attempt to pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect.’ ”

Since its passage, the MBTA has broadened its international scope (via treaties with Mexico, Japan, and Russia) and has protected additional species (adding eagles, hawks, and other birds in 1972, for example). In 1962 it was updated to address how Native American tribes can collect feathers from protected birds for religious ceremonies (a practice otherwise banned by the MBTA).

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

From audubon.org,

Duke Energy to Pay $1 Million for Bird Deaths at Wind Facilities

U.S. government issues the first criminal sentence for killing protected birds at turbine farms.

By Alisa Opar; November 27, 2013

Duke Energy’s 200-megawatt “Top of the World” wind project near Casper Wyoming.

The free pass is over. On Friday, Duke Energy Renewables pleaded guilty to the deaths of more than 150 protected birds at two of its Wyoming wind power sites and agreed to pay $1 million in fines. It marks the first time a wind energy company been prosecuted under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, despite the fact that numerous projects are known killing grounds of protected avian species.

“In this plea agreement, Duke Energy Renewables acknowledges that it constructed these wind projects in a manner it knew beforehand would likely result in avian deaths,” said Robert G. Dreher, Acting Assistant Attorney General for the Justice Department’s Environment and Natural Resources Division.

The Justice Department convicted the company—a subsidary of the North Carolina-based energy giant Duke Energy—of killing 14 golden eagles and 149 other birds, including including hawks, blackbirds, larks, wrens and sparrows, at its “Campbell Hill” and “Top of the World” projects between 2009 and 2013.

Of the $1 million, the $400,000 fine will go to the North American Wetlands Conservation Fund. The state of Wyoming will receive $100,000. The remainder will be used to purchase land or easements to protect golden eagle habitat and for projects that prevent golden eagle deaths at Wyoming turbines.

At the sites, the company will continue to employ field biologists who radio for turbines to be temporarily shut down when they spot an eagle, and to voluntarily report bird deaths to the government. And it’ll install new radar technology, similar to that used in Afghanistan to track incoming missiles. Duke will also have to submit a plan to cut down on avian deaths at its four Wyoming wind farms, and apply for an eagle take permit.

Bird advocacy groups applauded the settlement as an important step, but are pushing for more enforcement. “It takes more than one symbolic action to prove there is a real environmental cop on the beat,” Mike Daulton, vice president of government relations for the National Audubon Society, which supports properly sited wind projects, told Greenwire.

More convictions might be in the offing. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is investigating 18 bird-death cases involving wind-power facilities, reports the AP’s Dina Cappiello, and about a half dozen have been referred to the Justice Department.

The avian mortality at Duke’s two sites isn’t rare. Turbine’s spinning blades kill around a half-million birds a year, and even more bats. A study published in September in the Journal of Raptor Research found that wind farms in 10 states have killed at least 85 eagles since 1997, with most deaths occurring between in the last five years. Of those birds, 79 were golden eagles that struck wind turbines. (That doesn’t include the eagles killed by the decades-old turbines at California’s Altamont Pass.) The raptors smash into turbines because they don’t see them: When hunting, they keep their eyes on the ground, scanning for food.

Each of the mortalities is a violation of the federal Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, which could carry penalties of fines and jail time. To date, not a single wind energy facility has obtained a take (read: kill) permit, says Dalton.

Currently, there are few remedies for slashing bird deaths at existing sites. Only one option exists for making a turbine located in a high collision risk area safe: shutting it down when birds are flying nearby. One company is testing a remote-controlled system that allows operators in California stop spinning blades in Montana within 30 seconds of spotting an eagle. Other experimental measures under investigation include reducing prey near turbines and detecting and deterring birds from getting too close.

While the Duke case may indicate that the Obama administration is finally cracking down on this prevalent environmental crime, it also underscores the importance of better siting energy projects in the first place. That approach has helped ensure that wind projects have steered clear of critical grounds for greater sage-grouse in Wyoming and golden eagles in Montana.

The wind industry is only going to continue growing, and there’s clearly room for more renewables in the energy mix. And yes, cats and climate change pose bigger threats to birds than turbines. But given the risks they face, they need all they help they can get.

—————————————————————————————————————————————

Users Today : 13

Users Today : 13 Users Yesterday : 10

Users Yesterday : 10 Users Last 7 days : 90

Users Last 7 days : 90 Users Last 30 days : 334

Users Last 30 days : 334 Users This Month : 299

Users This Month : 299 Users This Year : 1308

Users This Year : 1308 Total Users : 11926

Total Users : 11926 Views Today : 50

Views Today : 50 Views Yesterday : 16

Views Yesterday : 16 Views Last 7 days : 245

Views Last 7 days : 245 Views Last 30 days : 676

Views Last 30 days : 676 Views This Month : 620

Views This Month : 620 Views This Year : 3677

Views This Year : 3677 Total views : 22511

Total views : 22511 Who's Online : 0

Who's Online : 0